By The Torch - The Story of Leonard Billings

Leonard Lorenzo Billings, born in Canton in 1843.

(Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Leonard Lorenzo Billings awoke early on a crisp autumn day in 1860. The walk from his home to Canton Junction took less than twenty minutes. Boarding the train to Boston, Billings was at the age where he was awakened. At age seventeen, Billings’ soul had been stirred by the Party of Lincoln. That October day would set the trajectory for a lifetime of experiences that would culminate in Billings’ death at the ripe old age of 96. The event that began it all was called the Wide Awake Procession in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Billings carried a torch high above his head and stood shoulder to shoulder with hundreds of other young men who were heeding the call from Abraham Lincoln.

In early March, 1860, Lincoln spoke in Hartford, Connecticut with a message that opposed the spread of slavery. Five store clerks, who had started a Republican group called the Wide Awakes, decided to join a parade for Lincoln, who had delighted in the torchlight escort back to his hotel provided for him after his speech. Soon, the Lincoln campaign made plans to develop Wide Awakes throughout the country and to use them to spearhead large voter registration drives, knowing that new voters and young voters tend to embrace new and young parties. The men who marched in these torchlight rallies were described by The New York Times as "...young men of character and energy, earnest in their Republican convictions and enthusiastic in prosecuting the canvass on which we have entered.”

Billings, was transformed immediately by the spectacle and the message. Billings wanted to fight in the War of the Rebellion. Each time he tried to enroll in the Union Army, he was turned away. “I tried to enlist several times but was rejected on account of my age and size. Finally, the Captain of Company D, 11th Massachusetts Infantry, allowed me to sign up. As a private I drilled with a gun on Boston Common during moonlight nights. On May 9, the 11th Massachusetts regiment, along with the 12th went to Fort Warren, Boston Harbor, to perform Garrison duty. There we drilled before and after breakfast, and most of the day, and I learned to be a soldier.”

Billings was puffed up with pride, he was taking his part in the civil war with both conviction and steadfast optimism. Disappointment soon followed. On June 17th, 1861 Billings was sent home prior to being sworn in for three years of service. “I cannot take him,” explained the Captain, “he is too young.” With that, Billings was sent back to his home in Canton. Not to be put off, he became a local volunteer assisting the organization of 101 officers and men into Company H, 29th Massachusetts Volunteers. Billings was precise, ordered and efficient. By November he was mustered into service and was sent to Fortress Monroe to train for battle.

From his first days in service, Billings witnessed the horror of war up close and personal. “While at Fortress Munroe, there was an exhibition of the merits of the “Sawyer” gun, a new type of steel gun, of large size, throwing a 60 pound shell. One shot was fired, the shell passing over to the opposite shore about 5 miles away, but in the firing the large gun split in pieces, killing three men of our regiment by crushing them to death. For months I had waited to see the gun tried out, and, on this occasion, placed myself in the rear on a pile of dirt to observe direction in sight. When the gun went off, I rushed back some distance to my tent and fell on the tent floor without a word. Then I jumped up, ran back, and found one large piece of the gun weighing 300 or 400 pounds on the pile of dirt I had just left and another piece nearby buried in the ground.”

There is no doubt that these near-death experiences were a frequent occurrence in the days that Billings saw service. And, Billings was clearly involved in major conflicts as a witness to history.

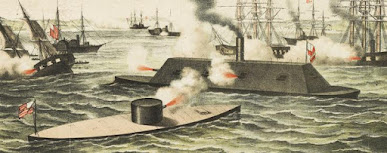

By the time that Billings was in his nineties, he was the only living man in America that witnessed firsthand the clash between the Merrimac

k and the Monitor off of Newport News, Virginia. Billings wrote vividly of the event in a memoir penned in May 1932. “About noon of March 8, our company’s drummer boy on duty at General Mansfield’s headquarters saw a lot of dark smoke at Elizabeth River from the dreaded Merrimack coming out from Norfolk, and sounded the long roll beat, which the slope Cumberland and Frigate Congress took up offshore. At the same time, word came the General Magruder (confederate) was outside with 6000 men. Slowly the Merrimack steamed up near us, hardly paying any attention to anyone, passed the sloops, and turned and sent huge shells at us witnesses on the bluff and into the camp. She then headed for the Sloop Cumberland, which, along with the Congress and our guns on shore, were shooting at her. The Merrimack soon struck the sloop amidships, opening a huge hole through which the sloop filled with water and sank quickly. All the wounded and sick, nearly 150 of the crew, went to the bottom, a few swimming to land, whom we waded in and helped. Then the Merrimack drew off, shelling our camp. Over the next two day, what Billings witnessed was the historically significant first battle between ironclad ships. Afterwards, one news article concluded that "naval architecture of the world, for all purposes of war, must be changed, and iron-plated steamers take the place of all the wooden constructions now in use." Billings recalled the battle the next day, “I asked the Captain if I could go over to the shore and was given permission. Shortly afterwards came the Merrimack. The Monitor, which lay at the wharf, moved out towards her, and then shots were exchanged as they got into position and found opportunity. 100 pound shots went over my head and landed in camp, every time the Merrimack came near our position. This was continued, both ships afraid of getting on the mud flats and both trying to force the other into that difficulty. Finally, the Merrimack withdrew to Elizabeth River on the way to Norfolk. These two days were a first real initiation in war. We were no longer recruits.”

Billings would later go on to be part of the Peninsula Campaign in 1861. This was a major Union operation launched in southeastern Virginia from March through July 1862, and was the first large-scale offensive in the Eastern Theater. The operation, commanded by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, was an amphibious turning movement against the Confederate States Army in Northern Virginia, intended to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond. As it turned out, General Robert E. Lee turned the subsequent Seven Day Battles into a humiliating Union defeat.

Billings was there, and was in retreat when “at the clearing in White Oak Swamp, we stopped for breakfast, but not for long, for soon the enemy came up and sent shell after shell exploding in our midst, severely cutting up the horses and mules, taking the Colonel’s arm off at the shoulder, and cutting others.”

August 1862 and into the fall, Billings found himself at Second Bull Run, Antietam and Fredericksburg. The descriptions that Billings shared are lurid. “Upon arrival, we found Jimmy Forbes, drummer boy for our company, with a wounded man. After placing the wounded man on the stretcher, he [Jimmy] stood up with his end and we started off. Just as he did so, a bullet struck him so near the jugular vein that he was turned around, dropped the stretcher, and caused the wounded man to roll off. Then Jimmy, a boy about 13 years old, was put on the stretcher and later taken to the hospital.”

Billings went on to join the Western Campaign and saw action in Mississippi, Vicksburg, Fort Sanders and Nashville, Tennessee. After three years and countless engagements with the enemy, Billings re-enlisted for another three years and received a bounty of $400.00 and a thirty day furlough. “In fact, we would’ve signed for 10 years in order to get out of this place. On the march my cowhide moccasins stuck in a hole and pulled off, leaving my bare feet on the ice and snow.” The long march, barefoot, to Knoxville took several days.

The trip back home was by steamer and by foot. “I proceeded through Louisville, Kentucky; Columbus, Ohio; and Albany, New York, to Boston.” Once home, Billings “procured an officer’s dress coat, with a pair of dark blue pants and a cap, shirts, and a number of things new and clean. Then I took a trip with my father on the train to Readville and walked 5 miles to Dedham Road in our old homestead where Hattie, Kate Manscroft, mother, and Uncle George lived.” A mere boy when he entered the war, the now twenty-one year old Billings was home. The stay would be short lived, Billings was about to become an officer in the 35th United States Regiment of Colored Troops. What was to come next would forever cement this man of honor squarely on the side of “liberty and justice for all.”

The 35th U.S. Colored Troop

The book is thick and heavy with a leather cover, gilded pages and a brass clasp. From a distance it is imposing, and up close it instantly bears the weight of history. Embossed on the cover in gold leaf reads “Officers Association, 35th Reg’t U.S. Colored Troops.” There is no doubt that this is a book that embodies our national history and opens a long lost door into a time and place of pain, suffering and eventual emancipation of 3.9 million slaves. The book is nearby on my desk as I write this story. History vibrates from the photographs inside. This is a glimpse into a military history that started with the Emancipation Proclamation.

On September 22, 1862, President Abraham Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which declared that as of January 1, 1863, all enslaved people in the states currently engaged in rebellion against the Union “shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” But although it was presented chiefly as a military measure, the proclamation marked a crucial shift in Lincoln’s views on slavery. Emancipation would redefine the Civil War, turning it from a struggle to preserve the Union to one focused on ending slavery, and set a decisive course for how the nation would be reshaped after that historic conflict.

Upon hearing of the Proclamation, many slaves quickly escaped to Union lines as the Army units moved South. As the Union armies advanced through the Confederacy, thousands of slaves were freed each day until nearly approximately 3.9 million were freed by July 1865. Massachusetts was the first state to form Black regiments and send military the men as leaders to train former slaves to fight for the cause of freedom. Massachusetts’ Governor John A. Andrew called for men to lead experimental units who were, “young men of military experience, of firm anti-slavery principles, ambitious, superior to a vulgar contempt for color, and have faith in the capacity of colored men for military service.” This call perhaps produced more active abolitionists for the 54th and her sister regiment the 55th than any other regiment in the North. But, there is another regiment, the 35th that may not have received the same notoriety as the 55th and 54th, but is no less valiant and critical to the victory of the Union Army.

The 35th United States Colored Infantry was composed of African American enlisted men commanded by white officers and was authorized by the Bureau of Colored Troops which was created by the United States War Department on May 22, 1863. The Governor of Massachusetts, John Andrew, felt responsible for taking the lead in organizing black units. Andrew stated in the letter to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, "The truth is that unless we do it, in Massachusetts, it cannot be expected elsewhere. While, if we do it, others will ultimately, and indeed soon, follow."

In the same letter to Stanton, Andrew addressed the question of who would lead the brigade. It had to be a careful selection. The Governor believed that an officer chosen to lead black soldiers should support the idea of arming blacks or, in the best case, have abolitionist sentiments. In addition to these moral attributes, Andrew sought a colonel who had seen action in the war and proved his abilities. By late April he settled upon Colonel Edward A. Wild of the 35th Massachusetts. And, in turn, Wild looked to others for support when choosing officers to lead the new unit.

In the case of one individual, Leonard Lorenzo Billings of Canton, is revealed the political connections and the personal convictions that influenced Wild in his selection of officers. Billings had served as a corporal in the Twenty-ninth Massachusetts Volunteers and had seen combat. He was recommended to Wild by Edward W. Kinsley, a close friend of Governor Andrew who, in a letter of September 1863, included the governor's warm greeting and summarized the corporal Billings’ qualifications. "He is," wrote Kinsley, "Anti-Slavery. Temperance ultra--and a good soldier." Billings received a commission as a second lieutenant.

Billings would write, “upon arrival at Norfolk, I reported to General Wild, whom I found to be a fine man and an able general, as well as surgeon. Leaving him, I went to Fortress Monroe and was sworn in by general B.F. Butler, mustering officer, as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Volunteers. So began the second tour of duty of Billings who had seen the war at an early age and whose convictions carried him back against the wave rising to free fellow human beings.

The tide of the war had turned in the favor of the Union, and once again, Billings recalled firsthand the view from the southern lines. The recollections are searing. “going up broad river, we landed at Boyd’s Point, marching for three or four miles overland with four or five regiments in line of battle, intending to push the enemy and then charge. We pushed ahead all right and found the enemy. Firing a volley, we rushed at the rebels through the woods, field, and swamps, and away they went. Cannons opened up immediately, our force on the left had to fall back, and then we had to do the same. It was warm fighting for a time, our regiment losing 175 men killed, wounded, and missing, Colonel Beecher, Captain Whitney, Lieutenant Krebs, Lieutenant Stone and Lieutenant Ambler were either wounded or disappeared. The 54th and 55th Massachusetts regiment got it very severely. As for our regiment, after following back a distance and drawing the enemy out of the fort, we formed a line in an open field, along with a New York battery and a Captain Titus. While lying side-by-side with Captain Armstrong of our Company K, in front of the battery, a piece of wood and tin that held a canister together hit and scraped the captains head, after cutting his hat. After the battery had fired 55 charges, we were the first to rush the enemy, who broke and ran. It was now dark, and I was so wet with perspiration that I could wring the water out of my shirt.”

|

Lieutenant Colonel William N. Reed became the highest-ranking black line officer of the Union Army. Reed enlisted in 1863, served in the 35th USCT. Reed suffered a mortal gunshot wound at the Battle of Olustee Florida in February 1864, and died shortly after. (Courtesy of the Canton Historical Society)

Billings described in detail his life fighting side by side with former slaves, now as equals. On February 20, 1864, the 35th Regiment had taken part in the Battle of Olustee. It was the largest battle of the Civil War fought in Florida and involved more than 10,000 soldiers, including three regiments of US Colored Troops. When the five-hour fight was over, Confederate forces claimed victory, and Union soldiers retreated to Jacksonville, where some remained until the war ended 14 months later. Billings recalled, “the regiment lost two hundred and eighty men and thirteen officers killed and wounded.” |

The end of the war finds Billings at Mount Pleasant, overlooking the bay and harbor of Charleston, South Caroline. He wrote of the end of the war in a matter of fact tone. “On April 14, came to us the news of Lee’s surrender, and everyone went wild. On April 19, we hear of the death of Lincoln, and, as everyone is much excited from the events of the last few days, Company K is order to re-enter the city to occupy the upper guard house, Captain Armstrong and I, with 75 of the company, being instructed to police one half of the city from the Citadel to the neck. On May 3, General Johnson surrendered his army, formally ending the war. Three days later, on May 6, the rebels in front of us surrender and come into the city, where our job becomes very busy, since martial law is proclaimed and everyone must have a pass after 10 o’clock at night.”

|

A detail from the broadside

that listed the entire regiment. |

The legacy that Billings left behind is a window into the Civil War. The sixty-one page

recollection is neatly typed and written near the end of the soldier’s life. The book that contains the photos of the 45 officers of the 35th is exceedingly rare. And, in a large oaktag envelope are the two commissions that Billings received while in the 35th, along with citations from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. And, perhaps rarest yet is the large broadside that lists the men that led and fought – black names along white names, forever enshrined in the company roster. At the end of his service, Billings was the provost marshal in South Carolina during the reconstruction period. In the days before Lincoln’s assassination, Billings stood among those who reviewed the troops, and Billings frequently referred to that most proud moment in his life. Today, there are men and women in New Bern, North Carolina that have taken up the historical record of the 35th. For the last five years a resurgence of interest in the 35th Regiment has led to the creation of a reenactment unit, some members of which are direct descendants of the men that fought with Billings. New Bern was the seat of recruiting for the U.S. Colored Troops. It is a place that Billings would have known. The 35th represented some of the finest leaders along some of the finest fighters in the conflicts of the deep south and Florida.

Bernard George is a historian associated with today’s 35th Regiment. “The 35th did not have the media following that the Massachusetts 54th and 55th had. That said, they had a fine record.” And, George points out that in two cases there were black officers in the 35th. The company reverend and a very fine surgeon.

The book and all the material that Billings collected will be scanned and shared with the people of New Bern. Canton now has a new found cousin and history inexorably tied to the emancipation of the men and women from the dark chapter of slavery. We have Billings to thank for this glimpse of the record. And, Canton’s connection is a telling indicator of the strength and conviction of the men who hailed from here and died in faraway places under the banner of liberty.

|

| Billings at age 95 in Sharon, Massachusetts |

Billings’ final days were a whirlwind. In his 97th year, Billings decided to re-trace his Civil War service and started a 2000-mile motor trip south to visit the battlefields of his youth. Accompanied by his daughter, Billings died in Charleston, South Carolina on October 22, 1939. The old solider was brought back to his house in Sharon, Massachusetts. “Flags were at half-staff, and business halted while Sharon’s “grand old man” was born to his soldier grave in the Canton Corner Cemetery. Pallbearers from the local veterans post bore the flag draped casket to the line of march on Pleasant Street. School pupils, scouts and townsfolk stood by respectfully as the cortege passed. A volley was fired by the firing squad and taps who sounded by the post buglers.” Canton’s son was laid to rest with his father and at long last, the soldier came home. Special thanks to the members of the 35th U.S. Colored Troops Reenactment Group and historian Bernard George.